Doing Pragmatics Peter Grundy Pdf Creator

In pragmatics (a sub-field of linguistics), a hedge is a mitigating word, sound or construction used to lessen the impact of an utterance due to constraints on the interaction between the speaker and addressee, such as politeness, softening the blow, avoiding the appearance of bragging and others. Typically, they are adjectives or adverbs, but can also consist of clauses such as one use of tag questions. It could be regarded as a form of euphemism. Hedges are considered in linguistics to be tools of epistemic modality; allowing the speaker to signal his or her degree of confidence in a connected assertion.[1] Hedges are also used to distinguish items into multiple categories, where items can be in a certain category to an extent.[2]

- 1Hedges and their uses

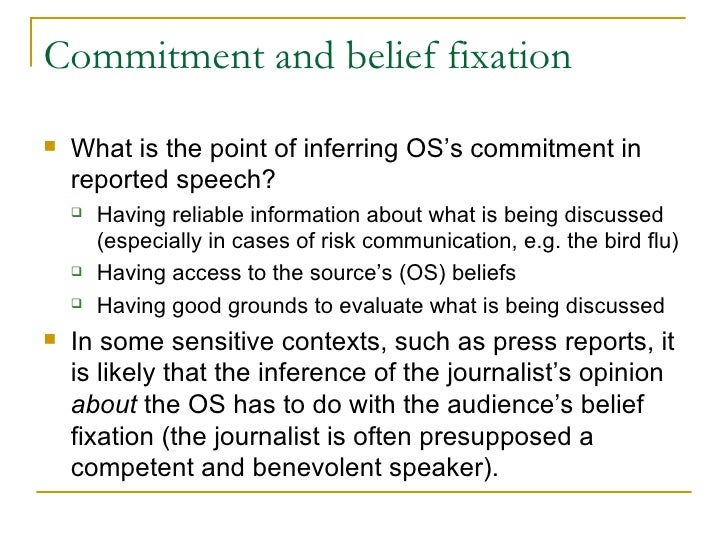

Pragmatic analysis of a fictional text. London and New York: Routledge. Grundy, Peter. (2000) Doing Pragmatics. London: Arnold. “Verbal Transcription 6 a.m.” in Collie, Joanne and Stephen Slater. (1995) Short Stories for Creative Language Classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pragmatics presentation chapter five from the book of peter grundy Doing Pragmatics 1. Presentation No.1 Subject: Pragmatics Topic: Implicit Meaning: Sperber and Wilson’s Relevance Theory Chapter Five Presented by Ijaz Ahmed Supervised by Dr. Iqbal Butt Discipline: Mphil in Linguistics. Create a clipboard. You just clipped your first slide!

Hedges and their uses[edit]

Hedges may take the form of many different parts of speech, for example:

- There might just be a few insignificant problems we need to address. (adjective)

- The party was somewhat spoiled by the return of the parents. (adverb)

- I'm not an expert but you might want to try restarting your computer. (clause)

- That's false, isn't it? (tag question clause)

Epistemic hedges[edit]

In some cases, 'I don't know' functions as a prepositioned hedge—a forward-looking stance marker displaying that the speaker is not fully committed to what follows in their turn of talk.[3]

Hedges may intentionally or unintentionally be employed in both spoken and written language since they are crucially important in communication. Hedges help speakers and writers indicate more precisely how the cooperative principle (expectations of quantity, quality, manner, and relevance) is observed in assessments[citation needed]. For example,

- All I know is smoking is harmful to your health.

- Here, it can be observed that information conveyed by the speaker is limited by adding all I know. By so saying, the speaker wants to inform that they are not only making an assertion but observing the maxim of quantity as well.

- They told me that they are married.

- If the speaker were to say simply They are married and did not know for sure if that were the case, they might violate the maxim of quality, since they were saying something that they do not know to be true or false. By prefacing the remark with They told me that, the speaker wants to confirm that they are observing the conversational maxim of quality.

- I am not sure if all of these are clear to you, but this is what I know.

- The above example shows that hedges are good indications the speakers are not only conscious of the maxim of manner, but they are also trying to observe them.

- By the way, you like this car?

- By using by the way, what has been said by the speakers is not relevant to the moment in which the conversation takes place. Such a hedge can be found in the middle of speakers' conversation as the speaker wants to switch to another topic that is different from the previous one. Therefore, by the way functions as a hedge indicating that the speaker wants to drift into another topic or to stop the previous topic.

Hedges in different languages[edit]

Hedges are used as a tool of communication and are found in all of the world's languages.[4] Examples of hedges in languages besides English are as follow:

- genre (French)

- Il était, genre, grand (He was, like, tall.)

- Ich weiß nicht (German)

- When this phrase has full syntactic complementation, speakers emphasize their lack of knowledge or display reluctance to answer. However, without an object complement, speakers display uncertainty about the truth of the following proposition or about its sufficiency as an answer.[5]

Hedges in fuzzy language[edit]

Fuzzy language is unclear or vague. Hedges can make sentences fuzzy or less fuzzy. Hedges in fuzzy language can be used to create sarcasm to make sentences more vague in written form.

- Sapphire works really hard.

- In this sentence, the word really can make the sentence fuzzy depending on the tone of the sentence. It could be serious (where Sapphire is really hard working and deserves a raise or promotion) or sarcastic (where Sapphire is not contributing to the work).

- Alejandra sure nailed her phonetics exam.

- In this sentence, sure is used with sarcasm to create vagueness.

Evasive hedging[edit]

Hedging can be used as an evasive tool. This can be used when expectations are not met or people avoid answering a question. This can be shown below:

- A: What did you think of Steve?

B: As far as I can tell, he seems like a good guy.

- A: What did you think about Erica's presentation?

B: I mean, it wasn't the best.

Politeness[edit]

Doing Pragmatics Peter Grundy Pdf Creator Online

Hedges can also be used to politely give commands and requests to others.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Ariel, Mira (2008), Pragmatics and Grammar, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ariel, Mira (2010), Defining Pragmatics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Benton, Matthew A. and Peter van Elswyk (2019), 'Hedged Assertion', in Goldberg, Sanford (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Assertion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grundy, Peter (2000), Doing Pragmatics, London: Arnold.

- Hurford, J.R. and B. Heasley (1997), Semantics: A Course Book, Ho Chi Minh City: Youth Press.

- Levinson, Stephen C. (1983), Pragmatics, Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas, Jenny (1995), Meaning in Interaction, Longman Group Limited.

Citations[edit]

- ^Kranich, Svenja (January 2011). 'To hedge or not to hedge: the use of epistemic modal expressions in popular science in English texts, English–German translations, and German original texts'. Text & Talk. 31: 77–99 – via De Gruyter.

- ^Fraser, Bruce (2010-08-26). 'Pragmatic Competence: The Case of Hedging'. New Approaches to Hedging. Studies in Pragmatics. 9: 15–34. doi:10.1163/9789004253247_003. ISBN9789004253247.

- ^Weatherall, Ann (October 2011). 'I don't know as a Prepositioned Epistemic Hedge'. Research on Language & Social Interaction. 44 (4): 317–337. doi:10.1080/08351813.2011.619310. ISSN0835-1813.

- ^Hennecke, Inga (June 2015). 'The impact of pragmatic markers and hedging on sentence comprehension: a case study of comme and genre'. Journal of French Language Studies. 27: 1–26 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^Helmer, Henrike; Reineke, Silke; Deppermann, Arnulf (December 2016). 'A range of uses of negative epistemic constructions in German: ICH WEIß NICHT as a resource for dispreferred actions'(PDF). Journal of Pragmatics. 106: 97–114. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.06.002. ISSN0378-2166.

External links[edit]

Teaching and Learning Pragmatics approaches language teaching from a sociocultural perspective and thus contributes to a current focus in ELT methodology. The book is divided into three parts. In the first part, the authors identify the area of pragmatics in which they are especially interested, in the second part, they focus on teaching pragmatics in the language classroom, and in the third part, turn to second-order pedagogical considerations. Approximately 60 per cent of the book is contributed by Ishihara, including virtually all of Part 2, with 20 per cent contributed by Cohen and 20 per cent jointly authored. The styles of the two authors are similar and the book as a whole reads seamlessly. The target readership is ‘pre-/in-service teachers and graduate students’ (p. 186), and for this reason, each chapter concludes with a series of reader-directed activities,...